Reimagining pie for the climate era

Three pies that can bring our food future into your kitchen right now

When you think of all the sustainable dishes that might add up to a cuisine fit for a warming world, you might not think of dessert, but you should. Food plays so many more roles than nutrition. It gives us comfort, daily doses of beauty, and something to connect over with loved ones. Cuisines just aren’t complete without dishes that carry meaning, so for me (and maybe you!), they’ve simply gotta have a serious sweet side.

What we eat—including dessert—needs to evolve for the climate era. Nearly every part of our food system is driving climate change, from how food is grown to how it gets to us and how much of it is wasted. And climate change is biting back, threatening food security, hurting farmworker health, and imperiling beloved ingredients.

Real food system change in the US will require change to big business and federal policy. But bakers and chefs—both at home and in professional kitchens—can help change happen faster. As Toni Cade Bambara wrote, “the role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible,” and imaginative baking can tempt us toward a climate cuisine.

In this newsletter, we’re going to imagine the baked goods that might spring from a regenerative, climate-friendly food system. And we’ll make plenty of them, too.

And in this inaugural edition of Pale Blue Tart, we’re starting smack-dab in the heart of the American dessert canon—with pie. Read on to learn about three pies we might be eating in the climate era. Then keep an eye out for the recipes this week and next, so you can bake up a better future, slice by slice.

Sky-high, plant-based key lime pie

One of the best ways to cut carbon is to scale back consumption of animal products like meat and dairy and swap more plant-based foods in their place. The modern animal agriculture industry is responsible for a stunning 14% of total global emissions, and wealthy and western diets contribute to that number disproportionately.

If you look at a side-by-side of food emissions, it’s clear reducing our red meat intake would be the biggest bang for our carbon buck. But as a baker, I think a lot about the middle-emissions ingredients like dairy and eggs, and how ubiquitously they exist in the background of recipes. I wonder: Are they sometimes there needlessly? Dairy, eggs, and gelatin play functional roles in desserts as often as they play flavor roles, lending creamy-smooth texture to a custard or giving gravity-defying lift to a meringue. The question is: Are they a crutch we could lose? In some cases, could we replicate those textures with plants?

An entire class of American pie—the custard pie—seems ready for a plant-based reimagining. Chocolate pies, lemon meringue, Boston cream, and key lime all top lists of America’s favorite pies. The greatest of these, my Floridian upbringing compels me to shout while I have your ear, is key lime. Its most famous ingredient may be the namesake citrus, but its most important one is less romantic: sweetened condensed milk. The processed dairy gloop is responsible for key lime pie’s quintessential silkiness, and seems to have been a crucial ingredient from the beginning. Cookbook author Stella Parks ruffled Floridian feathers in 2018 when she traced the oldest-known key lime pie recipe not to the Keys, but to the New York test kitchen of the Borden Milk Company in 1931, which was looking for a new way to hawk their milk-adjacent invention.

As we imagine how Florida’s state pie could evolve, we can look to other recipes and food cultures. Typical vegan key lime pie recipes use soaked cashews in the filling, but that creates a fudgy, cheesecake-like texture that doesn’t do my favorite tangy dessert justice. Any key lime pie worth its salt has gotta wobble. Desserts like Puerto Rican Tembleque and Chinese Tofu Pudding wobble admirably, and gave me ideas for a dairy-free filling. The recipe is coming later this week, and I want to know your honest judgments if you make it. If you were a 1930s dairy magnate, would this key lime pie pass muster?

Perennial grain tart

When European colonizers arrived in the Great Plains, they found topsoil 14 to 16 inches deep—nearly unrivaled across the world except in a few places like Argentina and Ukraine. That richness created such agricultural productivity that it earned the area a nickname: America’s breadbasket. But a century on, that productivity is beginning to dwindle as we’ve spent down the region’s topsoil reserve, using farming methods the writer Verlyn Klinkenborg likened to “slow strip-mining.”

Conventional grain farming relies on annual crops that are tilled and reseeded each year, leaving the soil root-free, loose, and prone to erosion. The loss of this fertile “A-horizon” hurts yields, and also makes it harder for the ground to store water during the hotter periods and variable rainfall that climate change will make more common.

But perennial grains, which have begun to tiptoe onto the market in recent years, could change that. Unlike annual crops and their wispy roots, perennials like Kernza—a cousin of bread wheat developed by The Land Institute—push roots 10 feet into the soil, holding it fast against wind and rain. Kernza and other perennial grains are still early in development and will need more investment to scale, but they hold promise for rebuilding soil and farmland climate resilience.

Kernza flour also holds culinary promise, as I learned the first time I baked bread with it in 2021. I thought I was losing it. The smell wafting from my oven was a degree or two off-center from cinnamon—sweet, nutty, and a world away from the muted warmth of a standard bread-flour loaf. But it turned out I hadn’t made a cinnamon-raisin loaf and completely blanked. I was just smelling Kernza’s particular, dessert-like bouquet.

It reminds me of the toasty-nuttiness of Brittany shortbread, which is my favorite French tart crust. (And the easiest, since you don’t have to roll out the dough.) Next week I’ll share a recipe for a Kernza tarte aux fraises that I hope will expand your pie and perennial-baking horizons.

Pawpaw chess pie

Scientists estimate there are tens of thousands of edible plants across the globe, but 75% of the food people eat comes from just 12 plants and five animals. The modern industrial food system has shrunk our food pyramid to a pinprick in its race to optimize for yield and transportability. And agrobiodiversity—nature’s insurance policy against disease, pests, and climate change—has become collateral damage.

This biodiversity race to the bottom is visible everywhere from the grocery store to bakeries. Sweets and baked goods are often made of just a few processed ingredients like refined cane sugar and bleached bread flour. The latter comes from a species that makes up 90-95% of wheat grown worldwide. But agricultural uniformity doesn’t stop at the pie crust—it extends to fruit, too.

The phrase “there’s nothing more American than apple pie” barely exaggerates the fruit farming situation in the US. Apples trail only grapes and oranges in cultivated acreage. But if we look beyond commodity agriculture to indigenous food sovereignty efforts, seed-saving projects, and backyard foraging, the US is a wonderland of edible fruit. It makes me wonder, what if pie were a canvas for biodiversity rather than food sameness?

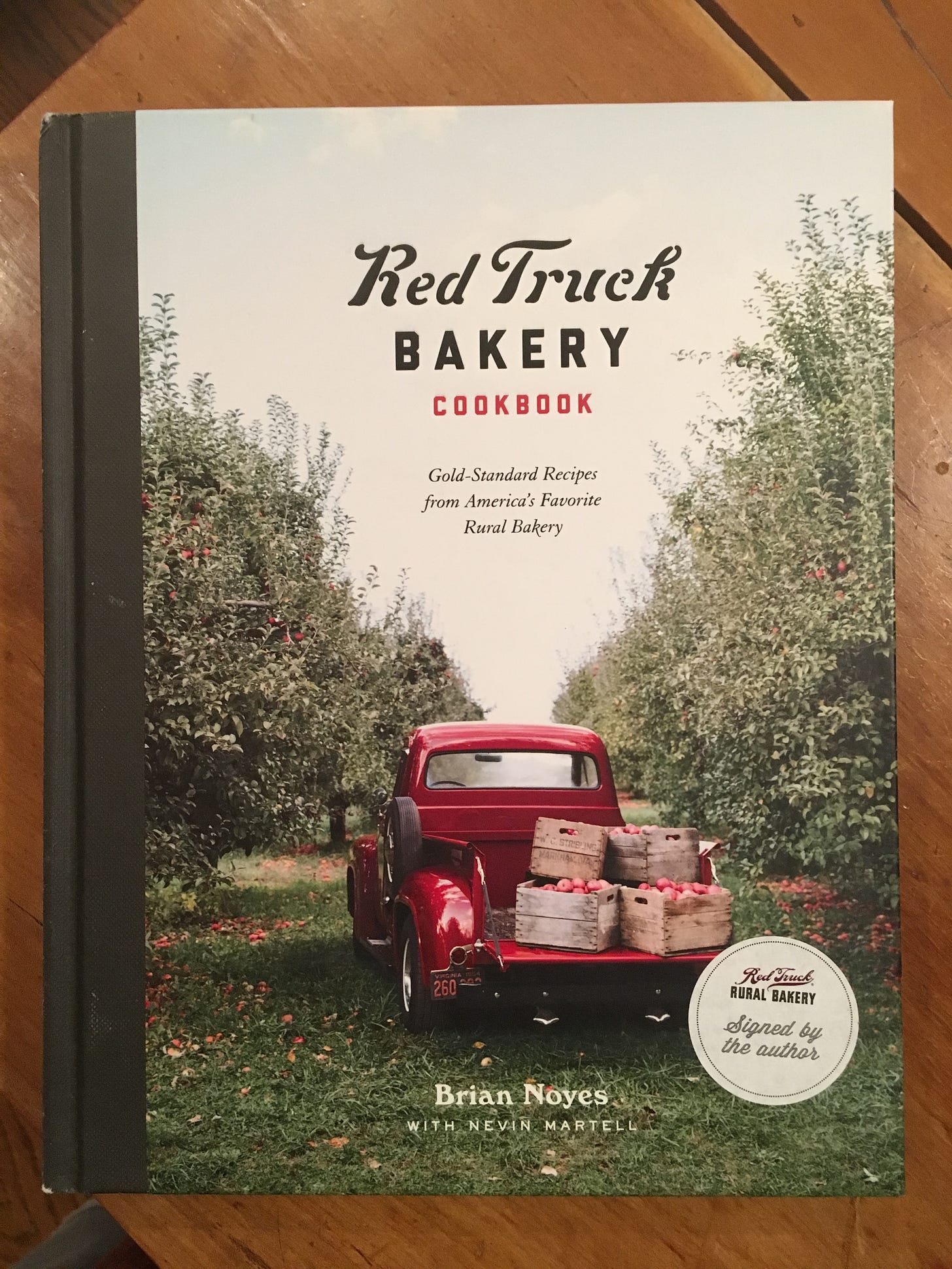

One of my favorite bakeries, The Red Truck Bakery in Marshall, Virginia, has a recipe in their namesake cookbook for pawpaw chess pie. The pawpaw is native to much of the eastern US, and was a common food source for Indigenous people before colonization. It has brilliant yellow flesh, a custardy texture, and a flavor somewhere between a mango and a banana. Today foragers find it growing along Appalachian streams and rivers, and the rest of us can buy it at farmers markets or online in late summer and early fall. For those of you in the pawpaw zone, the recipe—generously shared by Brian Noyes—is coming next week.

For those who live elsewhere, let this pie be your invitation to imagine. Butter, flour, and sugar can sing backup for whatever wild and native fruits thrive near you. For more fruit ideas, check out desserts by chefs like Sean Sherman and Freddie Bitsoie, whose work reviving Indigenous cuisines includes North American fruits like prickly pear, huckleberries, and juneberries. Wherever you live and whatever the season, dessert gets delicious fast when you think beyond the grocery store.

Thanks for reading! If this sparked ideas or questions, leave a comment and let me know. Also leave a comment if it made you think of a pie you’ve seen recently that belongs on a climate-era dessert menu. This is a gotta-catch-’em-all situation.

I'm hooked! I can't wait for recipes!

Incredible, thoughtful, dare I say, beautiful writing. Look forward to reading (eating) future pieces (slices?)!