One thing I know I want on the menu this Thanksgiving: more flavors! The world has 300,000 edible plants, so it’s a culinary (and environmental) bummer-and-a-half that most of our calories come from just 17 foods. One of those 17 is triticum aestivum, or the wheat in the flour we use in bread, cake, and yes—Thanksgiving pie crusts.

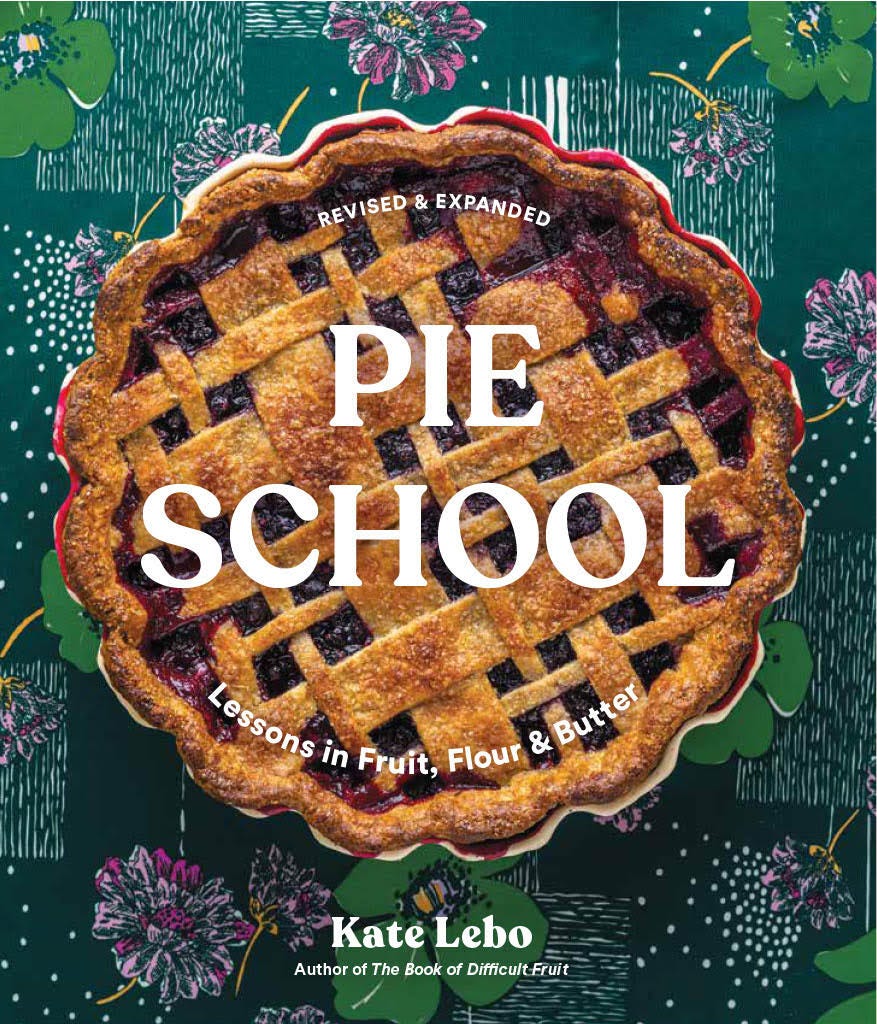

I’m always trying to take baby steps away from all-purpose flour, adding a smidge of mild oat to cake batter, or a devil-may-care handful of cinnamon-y Kernza to graham crackers. But while you can typically sub up to a quarter of the flour in any given recipe for a whole-grain one, baking with 100% whole grains requires a dash of know-how. That’s where Kate Lebo comes in. The cookbook author, essayist1, and cheesemaker released an updated version of her classic Pie School this summer, and among its new additions are recipes and techniques for pie crusts made with local and whole grains.

As she tells us in the Q&A below, some grains like Sonora wheat create extra-buttery flavor and that great American piecrust dream—flake. Others, like buckwheat, offer bold new flavors and a cookie-crumbly texture we flakehards didn’t even know to dream of. So whether visions of pumpkin, pecan, or Kate’s black-currant custard dance in your head as Turkey Day approaches, she has tips for whole-grain piecrust success. Shove the glasses up the bridge of your nose, and read on!

Q&A with Kate Lebo: Tips for whole-grain piecrust success

The following Q&A has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Caroline: Kate! It caught my eye that in the revised edition of Pie School, you added new recipes for pie crusts made with local and whole grains beyond traditional all-purpose. So what was it that made you start using whole-grain flours for pie?

Kate: What originally drew me was a bakery in my hometown of Spokane, Culture Breads. They've got a close relationship with a farm on the Idaho-Washington border called Palouse Heritage that does heritage grains. And it had never occurred to me, although I’ve lived in Spokane for almost a decade, that I live less than an hour from some of the best wheat-growing land in the world.

So I started eating at this place and was totally wowed by the flavors that they had, the textures that they were able to harness. So then I started talking to the guy that owns the place, Shaun Duffy, and one of the bakers. And from those conversations, I started to understand how rooted in place their baking was.

Before this, I had been thinking about how to source my ingredients in terms of fruit, meat, vegetables. But it hadn't occurred to me to think about: Where does my flour come from? I think that like with milk or a lot of different commodities, I had gotten used to going to the grocery store and grabbing a handle of milk or a bag of King Arthur or Gold Medal. I never really questioned what it was, and it was nice that it was consistent. It was always there.

But that consistency also made me take for granted what it was and where it was coming from. I have these stoner moments when I'm making cheese, where I’m like: “Man, cheese is just preserved milk. Whoa.” And I mean, duh, of course it is. That’s always been true. But I had forgotten that until I started making cheese. And it’s the same with flours. Until I started using local whole grains, I forgot that flour doesn't necessarily mean wheat. Flour just describes something that's been ground. There are many, many, many kinds of flour, and many, many different ways that we can bake with many different kinds of flour.

So encountering this bakery got me thinking about how I could become more of my place. I got curious about: What would pie taste like if everything about it was made within 60 miles of my house?

Caroline: OK, let’s talk pie crust. We’ll get into tips for whole-grain pie crust, but let’s start with the baseline of how to make a good standard pie dough, because that’s a bit of an art in and of itself. You write in Pie School that "American-style pie crust privileges the flake above all other textures." So how do you get good flake?

Kate: If I want to get a really flaky pie crust you need the dough to just come together, but it actually starts even before that. You need super cold fat, but not frozen, because if it's frozen you can't work it with your hands. You need to pay attention to what's going on in your bowl, and how as you bring that fat and flour together, they start to just barely contain each other—they're not going to perfectly mix. I love that little detail as a metaphor for how we’re in relationship with other people that we’re close with: We don't want to overwhelm and take each other over, we want to help contain each other, but have our separate identities.

Then when you add the water, you add enough that it just comes together. Flour is hydrophilic—it loves water. So where it's been stored, how old it is, the weather, all really matters, because it changes how much water you need to add to make the dough just come together. So to create really flaky dough, my secret is to know what you're looking for in that bowl, and to not actually measure your water at all, because on any given day you might want more or less. (I detail all this in Pie School. There are pictures!)

Also, the reason I say to go for flake in addition to taste is that with a flaky pie crust, it has enough structure that you can usually pick up the last bite, which I find delightful. There's something great about the way that pastry shattering on your fork looks and feels.

That said, a crumbly pie dough can also be really delicious. That happens if you overwork your dough, or if you don't have cold enough butter. It’s still delicious; it tastes kind of cookie-like. It's not my ideal, but it's probably somebody's ideal. There are lots of different textures people might look for.

Caroline: So I’m guessing locality is what pointed you to the whole grain flours you started working with?

Kate: Yes. What I had access to that worked really well was Sonora and spelt. And Culture Grains had all sorts of other kinds of grains, but they were good for bread-making, so I didn’t want to use those in pie. I also wanted the recipes to transfer to another locale, and I found those two flours were easy to find through a Google search.

Caroline: You have recipes in Pie School for crusts made with einkorn, Sonora, spelt, and buckwheat. Give us a teensy crash course in a couple of those grains (or seeds, in the case of buckwheat).

Kate: Einkorn is one of the most accessible flours people can find. I use the Jovial brand whole-grain einkorn. That flour has a cross between a flaky and a cookie-like texture, and it's got this nice, cereal-like flavor (which might not translate as being a nice flavor, but I mean it as a compliment!). There are pies in the book that it goes particularly well with, like sarvisberry (aka serviceberry). But with einkorn, you could sub that for any old pie and it probably would work well.

My very favorite flavor is Sonora white wheat. It’s really buttery, toasty, and just a delicious texture, and it’s one you can make flaky. And to have a flaky pastry with that flavor? I mean, this is also what got me into the whole grains, is getting excited by different flavors—flavors of place, yes, but also just deeper notes than plain-old, all-purpose (AP) flour.

The secret to that one is that you’ve got to get a flour that's been ground coarse enough that some of the bran is still big enough to sift out. You want the bran present, but you sift it out because bran can prevent pie dough from getting a nice flake. Then you make your dough. And when it’s time to roll it, you roll your dough in the bran. You want the bran for the flavor, so that’s the way to get it back in.

The buckwheat pie crust is an old recipe I designed because I wanted to make a gluten-free recipe. The thing about gluten-free flours is that when you make the gluten-free dough, it's not going to be elastic the way a gluten-full dough will be. So it can be flaky, but you're going to have trouble rolling it out the way that you're used to, if you're used to gluten-full flours. It's going to probably be more of that cookie-crumbly texture that I was talking about. And also, buckwheat has such a strong flavor—I found that sometimes it would overwhelm and clash with some fruits. I really like it with peach, blueberry, or apple.

Caroline: So the flour sifting is one trick to whole-grain pie crusts. What about water?

Kate: Whole-grain flours are thirstier, and take longer to hydrate. I have the best luck with whole-grain pie crusts when I let them rest overnight. A standard all-purpose crust calls for 5 to 8 tablespoons of water, but if I did that with a whole-grain crust, it would be stubborn and hard and annoying. What you’re looking for in whole grain is usually around 9 tablespoons of water—maybe 10.

And what you want to look for is actually feeling the presence of water: It’s going to feel tacky, but not sticky. When you touch the dough, you’ll hear your finger peeling away from it, because of that right amount of water. If you can hear that, that’s the correct amount.

The other thing is that if you’re already used to making AP-flour pie dough, you’ll know you’ve added the right amount of water when you’re like: Oh sh*t, this is too much water.

Caroline: OK, let’s recap. What are the most important tips if somebody is going to experiment with a whole-grain pie crust for the first time this Thanksgiving? (I’ll be in that boat.)

Kate: First, Make sure you’re comfortable with that traditional, all-purpose pie crust. That’s pie 101. Once you get your technique down with that, you’re ready to go to varsity pie. Then either work with Einkorn flour—because it’s probably easiest to find—or with Sonora white wheat, because that’s relatively easy to work with. Then remember the water situation: You need more of it. Then let the dough rest overnight in your fridge, and you’ll have a better time rolling it out. Other than that, it’ll behave like an all-purpose pie crust.

Caroline: Oh and! I’m doing a special Friendsgiving surprise thingee2 on the newsletter next week, which made me want to ask you: What pie from Pie School would you bring to a Friendsgiving?

Kate: I’d bring Winter Luxury Pumpkin Pie. Although I haven’t actually been able to get a hold of a Winter Luxury pumpkin for two years now, so really what I mean is just find yourself a fantastic heirloom pumpkin or squash. My second favorite after Winter Luxury is a Red Curry squash. I’ll roast the squash then process it in my food mill and freeze it so it’s all ready to go. The depth of flavor of these heirloom squashes and pumpkins make that pie outta sight. My husband doesn’t like pumpkin pie, but this I can get him to eat.

Kate’s essay collection The Book of Difficult Fruit is dazzling. Bits of it weave like lattice into her updated version of Pie School.

Next week we got a lil something special and unusual for this dessert newsletter, and it’s coming on Thursday instead of the normal Tuesday. Gird thine appetites!

Thanks for sharing this! I've been wanting to experiment with more whole-grain tart doughs, and this is very helpful. Also — Kernza graham crackers! Brilliant! Perfect use for Kernza!